Emma Wallbanks

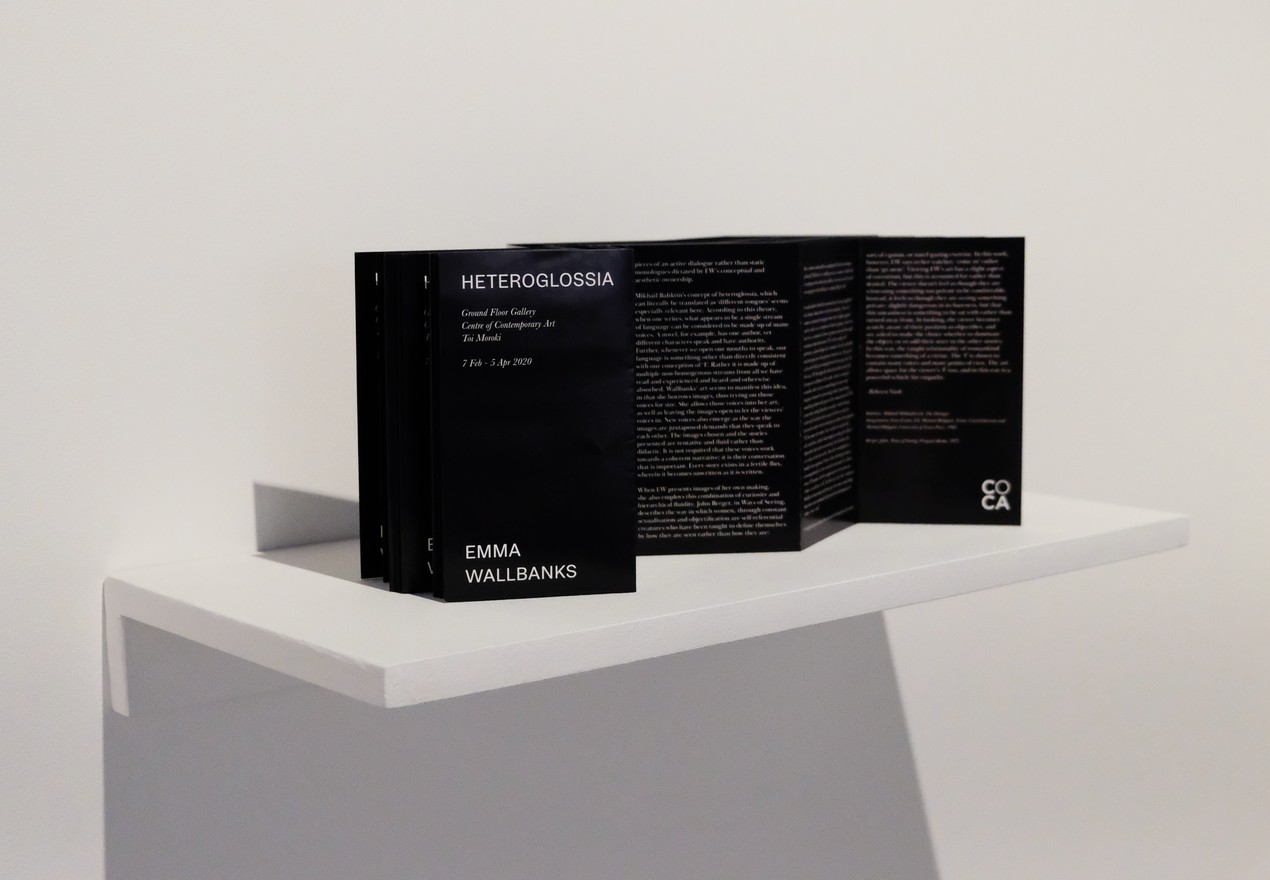

Heteroglossia Publication

Emma Wallbanks

Heteroglossia Publication

Emma Wallbanks’ work sometimes looks out from the position of her-self and, at other times, works to scrutinise her-self. It is sometimes collected; the privacy of others’ photographs co-opted, and sometimes is created for the purpose of being shown. What brings these objects (with disparate elements) together is EW’s ability to create spaces for emotion in her works. In all cases, she asks the viewer to engage with a complex range of human feeling, where contradicting emotions are able to sit next to each other without needing to be reconciled. Another subterranean binding material is EW’s subtle yet thorough destruction of traditional hierarchical binaries. Man does not dominate Woman, and images slip out of the private and into the public space and back again with ease. The ‘emotional response’ wriggles out from under the dominance of the ‘intellectual response’, and is presented as a legitimate position from which to make art, as well as to absorb and read that art.

When EW collects imagery; when she steals slides from op shops, she is not looking for ready mades. Her process, rather, is one of empathetic gathering, where she finds objects that seem partly-made. The images are either imperfect (bad lighting, blurred etc.), or else defy neat story-telling (offer multiple possible interpretations). EW epmathetically connects to these anonymous people and their flawed/open ended image-making, and instead of appropriating their images, she elevates them into unintentional artists. EW also elevates her viewers into unintentional story-tellers who must, as she has, form connections to and narratives from the collected images. The images offer connection between unknown original creator, herself and her viewers, and thus are pieces of an active dialogue rather than a static monologue dictated by EW’s conceptual and aesthetic ownership.

Mikhail Bahktin’s concept of heteroglossia, which can literally be translated as ‘different tongues’ seems especially relevant here. According to this theory, when one writes, what appears to be a single stream of language can be considered to be made up of many voices. A novel, for example, has one author, yet different characters speak and have authority. Further, whenever we open our mouths to speak, our language is something other than directly consistent with our conception of ‘I’. Rather it is made up of multiple non-homogenous streams from all we have read and experienced and heard and otherwise absorbed. Wallbanks’ art seems to manifest this idea, in that she borrows images, thus trying on those voices for size. She allows those voices into her art, as well as leaving the images open to let the viewers’ voices in. New voices also emerge as the way the images are juxtaposed demands that they speak to each other. The images chosen and the stories presented are tentative and fluid rather than didactic. It is not required that these voices work towards a coherent narrative; it is their conversation that is important. Every story exists in a fertile flux, wherein it becomes unwritten as it is written.

When EW presents images of her own making, she also employs this combination of curiosity and hierarchical fluidity. John Berger, in Ways of Seeing, describes the way in which women, through constant sexualisation and objectification are self-referential creatures who have been taught to define themselves by how they are seen rather than how they are:

She is almost continually accompanied by her own image of herself. Whilst she is walking across a room or whilst she is weeping at the death of her father, she can scarcely avoid envisaging herself walking or weeping (46)

I would add to this that women have been taught to feel shame about their self-referentiality. The way women constantly imagine how they might appear can be taken as a symptom of their egoism, where in fact it is a symptom of how egoism is denied through continual objectification. EW, in her nude self-portraits, acknowledges her inbuilt self-referentiality and incorporates this process into her art. She gazes at herself while presenting herself to be gazed at. In this way, EW disrupts the hierarchy inherent in the European tradition of the nude, where a woman’s sexuality only exists as something that men may imagine themselves possessing rather than being something inherently part of the woman herself. EW is not only saying that her sexuality/body belongs to herself, but that she is aware of the way in that she has learned to only exist in relation to others. In response, EW becomes the other/the watcher as well as the self, and thus, rather than simply turning the object/objectifier hierarchy on its head, she dissolves the very idea of the hierarchy. She offers multiplicity; a bodily heteroglossia. If one of the defining features of womanhood is to be watched constantly by others, then, EW posits, the best approach is to become an ‘other’ as well as a ‘self’. In this way, the ‘she’ embraces fluidity of meaning and the gaze becomes something that does not automatically posit the dominance of ‘other’ over ‘self’.

It might appear that this sort of self-analysis is its own sort of egoism, or naval gazing exercise. In this work, however, EW says to her watcher, ‘come in’ rather than ‘go away’. Viewing EW’s art has a slight aspect of voyeurism, but this is accounted for rather than denied. The viewer doesn’t feel as though they are witnessing something too private to be comfortable. Instead, it feels as though they are seeing something private; slightly dangerous in its bareness, but that this uneasiness is something to be sat with rather than turned away from. In looking, the viewer becomes acutely aware of their position as objectifier, and are asked to make the choice whether to dominate the object, or to add their story to the other stories. In this way, the taught relationality of womankind becomes something of a virtue. The ‘I’ is shown to contain many voices and many points of view. The art allows space for the viewer’s ‘I’ too, and in this way is a powerful vehicle for empathy.

Essay written by Rebecca Nash for Heteroglossia, 2020. Designed by Sophia Johnston.