25.05.16

07.08.16

Both artists investigate personal and collective histories, memory about cultural, ethnic and personal identity, and the impact of colonialism, from African migration and Māori perspectives.

Heralded as one of the most important commissions of the Venice Biennale in 2015.

Vertigo Sea by Ghanaian born British artist filmmaker John Akomfrah is a mesmerising cinematic exploration of our relationship to the migration of refugees interplayed with awe inspiring imagery of the history, intelligence and majesty of the largest mammal on earth.

Whilst Akomfrah’s Vertigo Sea operates on a universal nature of the ocean as site, Bridget Reweti’s work is tied specifically to the land of Aotearoa New Zealand. Tirohanga takes the narratives of her iwi at Tauranga Moana as a starting point, to explore our understanding of the land and landscape in the North and South Island.

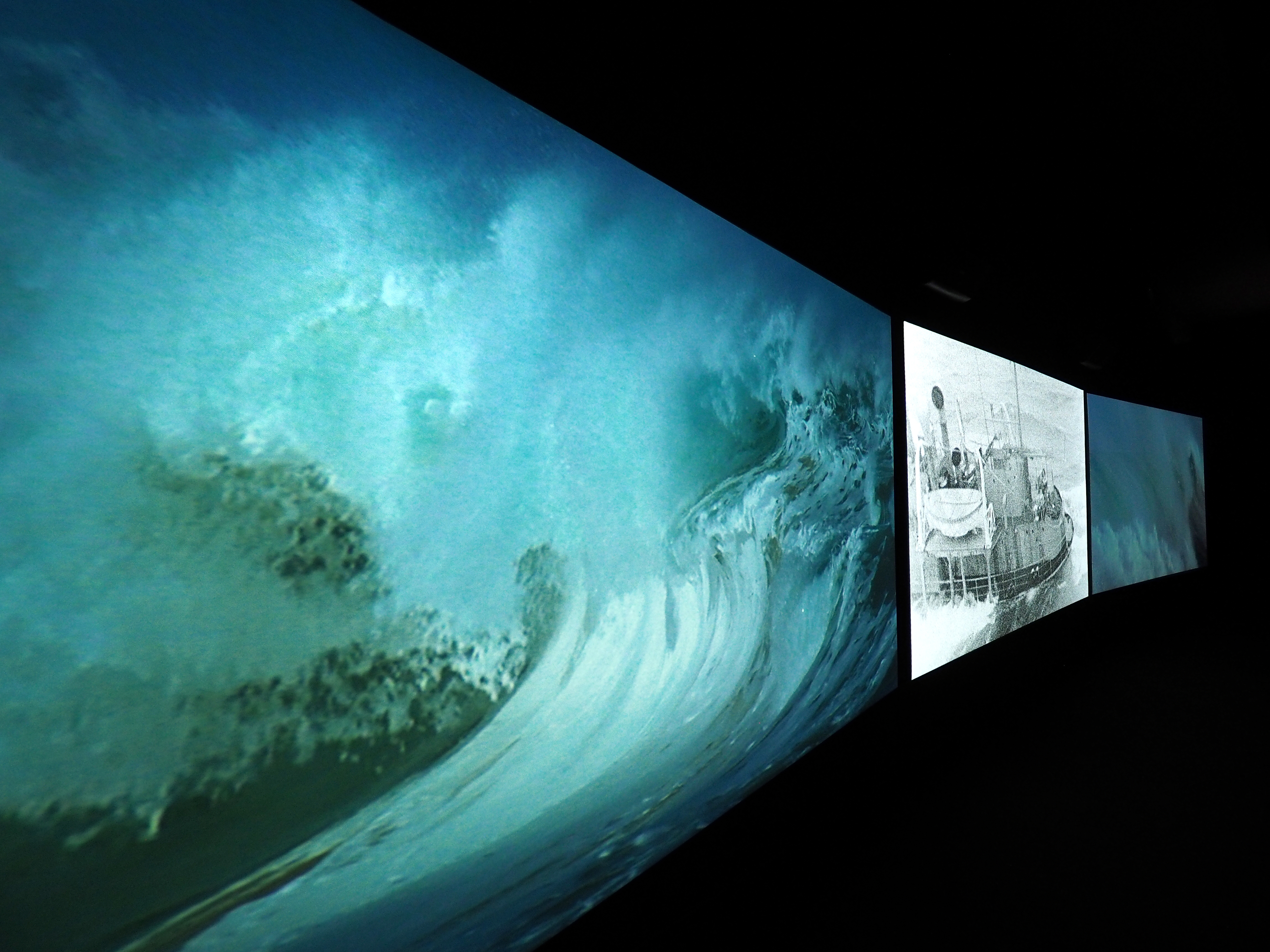

Vertigo Sea, a three-screen film, first seen at the 56th Venice Biennale 2015 as part of Okwui Enwezor’s All the World’s Futures exhibition, is a sensual, poetic and cohesive meditation on man’s relationship with the sea and exploration of its role in the history of slavery, migration, and conflict.

Fusing archival material, readings from classical sources, and newly shot footage, the work explicitly highlights the greed, horror and cruelty of the whaling industry. This material is then juxtaposed with shots of African migrants crossing the ocean in a journey fraught with danger in hopes of ‘better life’ and thus delivering a timely and potent reminder of the current issues around global migration, the refugee crisis, slavery, alongside ecological concerns.

Shot on the Isle of Skye, the Faroe Islands and the Northern regions of Norway, with the BBC’s Bristol based Natural History Unit, Vertigo Sea draws upon two remarkable books: Herman Melville’s Moby Dick (1851) and Heathcote Williams’ epic poem Whale Nation (1988), a harrowing and inspiring work which charts the history, intelligence and majesty of the largest mammal on earth.

John Akomfrah Vertigo Sea, 2015 Three channel colour video installation, 7.1 sound 48 minutes 30 seconds

John Akomfrah Vertigo Sea, 2015 Three channel colour video installation, 7.1 sound 48 minutes 30 seconds

John Akomfrah Vertigo Sea, 2015 Three channel colour video installation, 7.1 sound 48 minutes 30 seconds

John Akomfrah Vertigo Sea, 2015 Three channel colour video installation, 7.1 sound 48 minutes 30 seconds

John Akomfrah

John Akomfrah’s works are characterised by their investigations into memory, postcolonialism, temporality and aesthetics and often explore the experience of the African diaspora in Europe and the USA.

Akomfrah was a founding member of the influential Black Audio Film Collective, which started in London in 1982 alongside the artists David Lawson and Lina Gopaul, who he still collaborates with today.

His work has been shown in museums and exhibitions around the world including the Liverpool Biennial; Documenta 11, Centre Pompidou, the Serpentine Gallery; Tate; and Southbank Centre, and MoMA, New York. A major retrospective of Akomfrah’s gallery-based work with the Black Audio Film Collective premiered at FACT, Liverpool and Arnolfini, Bristol in 2007. His films have been included in international film festivals such as Cannes, Toronto, Sundance, amongst others.