Hayden Fowler

New World Order, 2013

Hayden Fowler

New World Order, 2013

New World Order, 2013

HD digital video, colour, sound, 15minutes 17 seconds

Courtesy of the artist

Hayden Fowler’s installations present a surreal, dystopian world where humans who lose connection with nature try to reconcile with it. Drawing on contemporary discussions around ecological destruction, genetic modification and the alienation of an increasingly urban society from the natural environment, Hayden’s work depicts places that merge scientific theory with popular culture.

In New World Order, a series of sliding vignettes show exotic, peculiar birds perched in grey woodland. Preening and calling, these are rare heritage bred chickens, their unusual plumages markedly different to the domestic fowl. The scene is bleak, inducing and engaging with Solastalgia, a term coined by the philosopher Glenn Albrecht, which describes the sense of helplessness and distress induced by the loss of our environment, natural ecosystems and biodiversity. In New World Order, the landscape is ashen and barren, perhaps a vision of a post-apocalyptic future. Trees are blackened and lifeless, the background is hazy and dense, like a stage set or film backdrop, or perhaps a dusty diorama in a strange museum. The birds call with unsettling electronic ringtones; a soundtrack imagined from a not so distant future where these birds have partially absorbed and ‘remember’ human technology. They appear completely at home in this dark place, but for the viewer, they’re unsettling, unnatural.

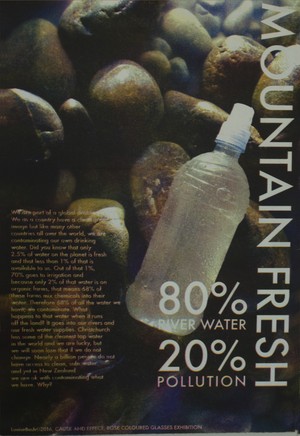

These scenes are both a future narrative and a reminder of our own histories. Aotearoa was once 80 percent covered in native forest; waves of migrants, both pacific and european, have burned and cleared the land to support our existence. A small island in the pacific, many of our bird species evolved in isolation away from mammalian predators. This made them larger, ground dwelling, and vulnerable to hunting by both humans and the animals that accompanied them in their settlement. Many species, both plant and animal, have not survived.

In response, we have created conservation estates; small eco sanctuaries, reimagined wetlands planted with native species, stands of native trees with predator proof fences. Places we can visit, but not remain. Nature is controlled by us, kept in stasis. Breeding programmes for our native kakapo and kiwi are celebrated as we keep these creatures from extinction by the faintest of margins. These conservation estates are celebrated in technicolour, bright hues and positive idyllic scenes; a stark contrast from Hayden’s monochromatic sets. Are these efforts enough? Do they sate our Solastalgia?

New World Order seeks to inspire a cathartic release experienced by imagining the world post-humans. Perhaps when watching we can imagine autonomous nature newly evolving amongst the apocalyptic ashes of our destruction. Fowler pushes us to question how we can think about and embrace new ecologies, or set up their genesis? It’s a difficult question to answer. For example, if Aotearoa were to return to an autonomous ecology, rather than a highly controlled human-dependant one, there would need to be either a total eradication of exotic predators, or a total acceptance of them, and acceptance of ongoing extinction.

Artworks

Taloi Havini and Stuart Miller

Blood Generation: Sami and the Panguna Mine, 2009

Gaby Montejo

Honeymoon Latte, 2016

Dryden Goodwin

Breathe, 2012

Natalie Robertson

Rangitukia Hikoi 0-14, 2016

Alex Monteith

Rena Shipping Container Disaster, 2011 (ongoing)

Hayden Fowler

New World Order, 2013

Anne Noble

Bruissement, 2015; No Vertical Song, 2015

Melissa Macleod

Drill (performance) 2016; Weight (installation) 2016

Tyne Gordon

Pooling, 2016

Zina Swanson

Plants from the sale table, 2016

Liv Worsnop

Practicool Planet; Dust Gatherings: Potential and Poison; Gang Patches; Lux & Plant Gang Chats, 2016

Tim Knowles

Glacial Creep - Haupapa Tasman Glacier

Precarious Nature - Extended Network

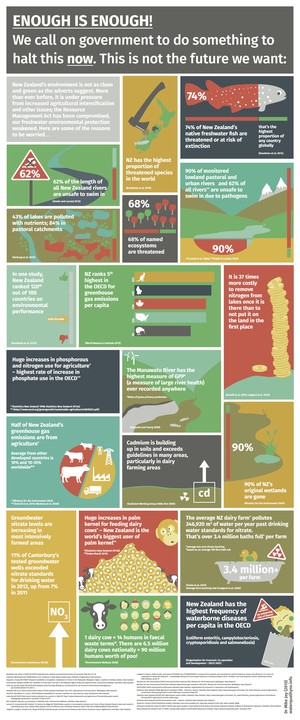

Mike Joy

Precarious Nature - Extended Network

Te Kōhaka o Tūhaitara Trust

Precarious Nature - Extended Network

Habitat for Humanity

Precarious Nature - Extended Network

Trees for Canterbury

Precarious Nature - Extended Network

Generation Zero

Precarious Nature - Extended Network

350 Christchurch